Risk-Free Asset, Preferences, and Optimization

Sukrit Mittal Franklin Templeton Investments

1. Why Add a Risk-Free Asset?

So far, all portfolios involved only risky assets.

That world is incomplete.

In reality, investors can always:

- Park money safely (treasury bills, government bonds)

- Borrow or lend at (approximately) risk-free rates

Ignoring this option distorts everything.

The risk-free asset is not an abstraction.

It is a foundational building block of modern finance.

2. Portfolio with One Risky Asset and One Risk-Free Asset

Let:

- \(R_f\) = risk-free return (constant, deterministic)

- \(R\) = return on a risky asset (random variable)

- \(\mu = \mathbb{E}[R]\) = expected return of risky asset

- \(\sigma = \text{SD}(R)\) = standard deviation of risky asset

- \(w\) = fraction of wealth invested in risky asset

- \(1-w\) = fraction invested in risk-free asset

Portfolio return:

\[ R_p = wR + (1-w)R_f \]

This is the simplest mixed portfolio.

Yet it already contains profound insights.

Expected Return

Taking expectations:

\[ \mathbb{E}[R_p] = w\mathbb{E}[R] + (1-w)R_f = w\mu + (1-w)R_f \]

Rearranging:

\[ \mu_p = R_f + w(\mu - R_f) \]

Interpretation:

- Base return: \(R_f\) (certain)

- Risk premium: \(w(\mu - R_f)\) (proportional to exposure)

The investor earns a premium only for bearing risk.

Linear in \(w\). Nothing surprising yet.

Risk of the Portfolio

Since \(R_f\) is constant, it has zero variance:

\[ \sigma_p^2 = \text{Var}(wR + (1-w)R_f) = w^2 \text{Var}(R) = w^2\sigma^2 \]

Therefore:

\[ \sigma_p = |w|\sigma \]

Key insight: All risk comes from the risky asset.

The risk-free asset contributes zero to portfolio volatility.

Risk scales linearly with exposure.

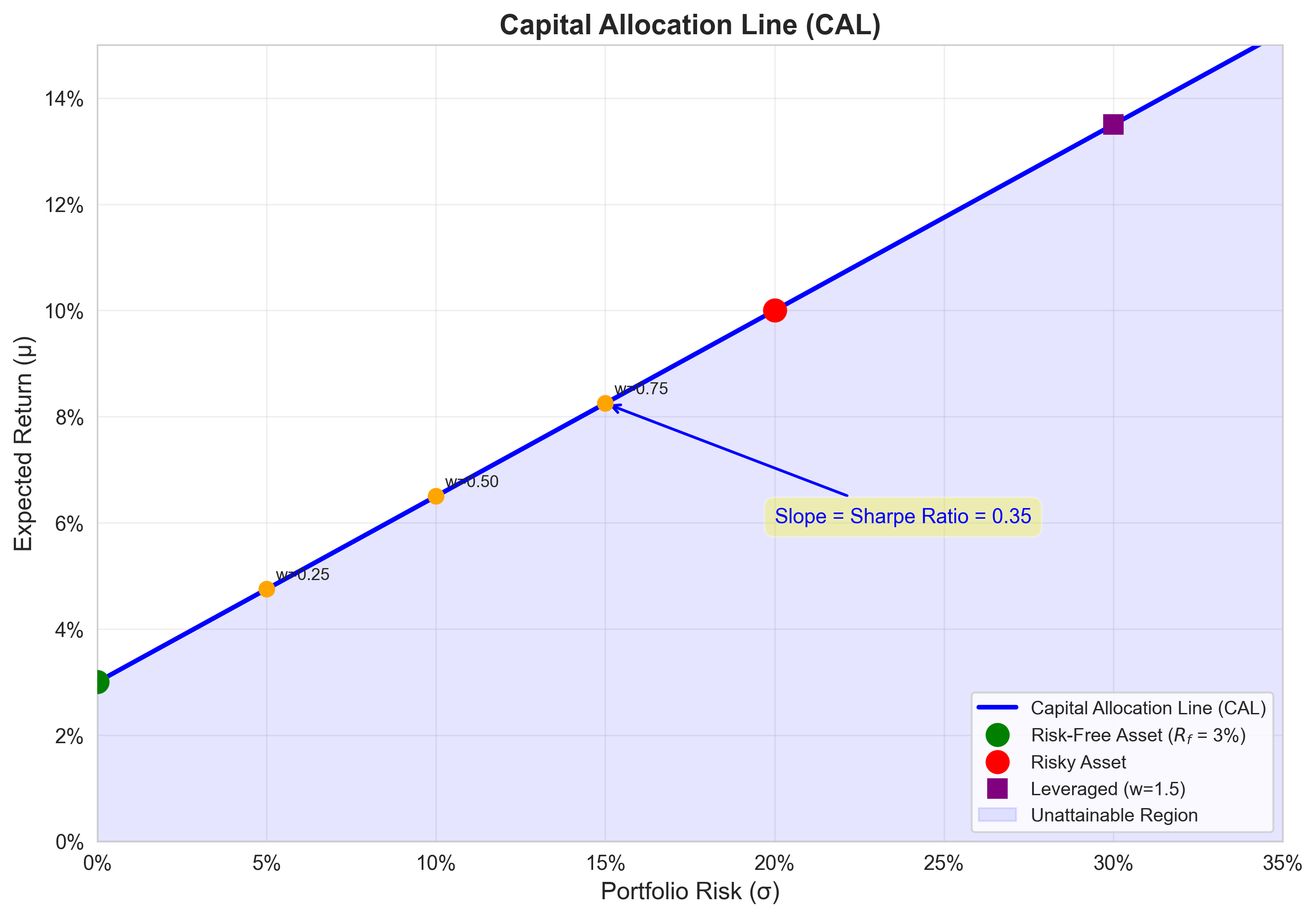

Interpretation of Weights

Case 1: \(0 < w < 1\) (Lending)

- Invest partially in risky asset

- Lend the rest at \(R_f\)

- Conservative strategy

Case 2: \(w = 1\)

- 100% in risky asset

- No borrowing or lending

Case 3: \(w > 1\) (Borrowing)

- Borrow at rate \(R_f\)

- Invest more than initial wealth in risky asset

- Levered strategy

Case 4: \(w < 0\)

- Short the risky asset

- Invest proceeds in risk-free asset

- Extremely conservative

3. Capital Allocation Line (CAL)

From the previous slide:

- \(\mu_p = R_f + w(\mu - R_f)\)

- \(\sigma_p = |w|\sigma\)

Solve for \(w\) from the second equation:

\[ w = \frac{\sigma_p}{\sigma} \]

Substitute into the first equation:

\[ \mu_p = R_f + \frac{\sigma_p}{\sigma}(\mu - R_f) \]

Rearranging:

\[ \boxed{\mu_p = R_f + \frac{\mu - R_f}{\sigma} \sigma_p} \]

This is the Capital Allocation Line (CAL).

Interpretation of the CAL

The CAL is a straight line in \((\sigma, \mu)\) space.

\[ \mu_p = R_f + \frac{\mu - R_f}{\sigma} \sigma_p \]

- Intercept: \(R_f\) (the risk-free rate)

- Slope: \(\frac{\mu - R_f}{\sigma}\) (reward per unit of risk)

The slope is called the Sharpe Ratio:

\[ \text{Sharpe Ratio} = \frac{\mu - R_f}{\sigma} \]

Interpretation:

- Measures excess return per unit of volatility

- Higher Sharpe ratio = better risk-adjusted performance

- Universal metric for comparing investment strategies

Markets reward efficiency, not bravery.

Graphical Representation

Key observations:

- Every point on the CAL is a portfolio combining \(R_f\) and the risky asset

- Points below the CAL are dominated (achievable with better risk-return)

- Points above the CAL are unattainable (given the assets)

- The CAL extends infinitely in both directions (leverage and short-selling)

The investor's problem: choose a point on the CAL.

Derivation: Why the CAL is Straight

We derived:

\[ \mu_p = R_f + \frac{\mu - R_f}{\sigma} \sigma_p \]

This is a linear equation in \(\sigma_p\).

Why linearity?

- Expected return is linear in weights: \(\mu_p = w\mu + (1-w)R_f\)

- Risk scales linearly with \(w\): \(\sigma_p = w\sigma\)

- Eliminating \(w\) preserves linearity

Contrast with risky assets only:

- Two risky assets form a hyperbola in \((\sigma, \mu)\) space

- Adding \(R_f\) "straightens" the efficient frontier

This geometric simplification is the power of the risk-free asset.

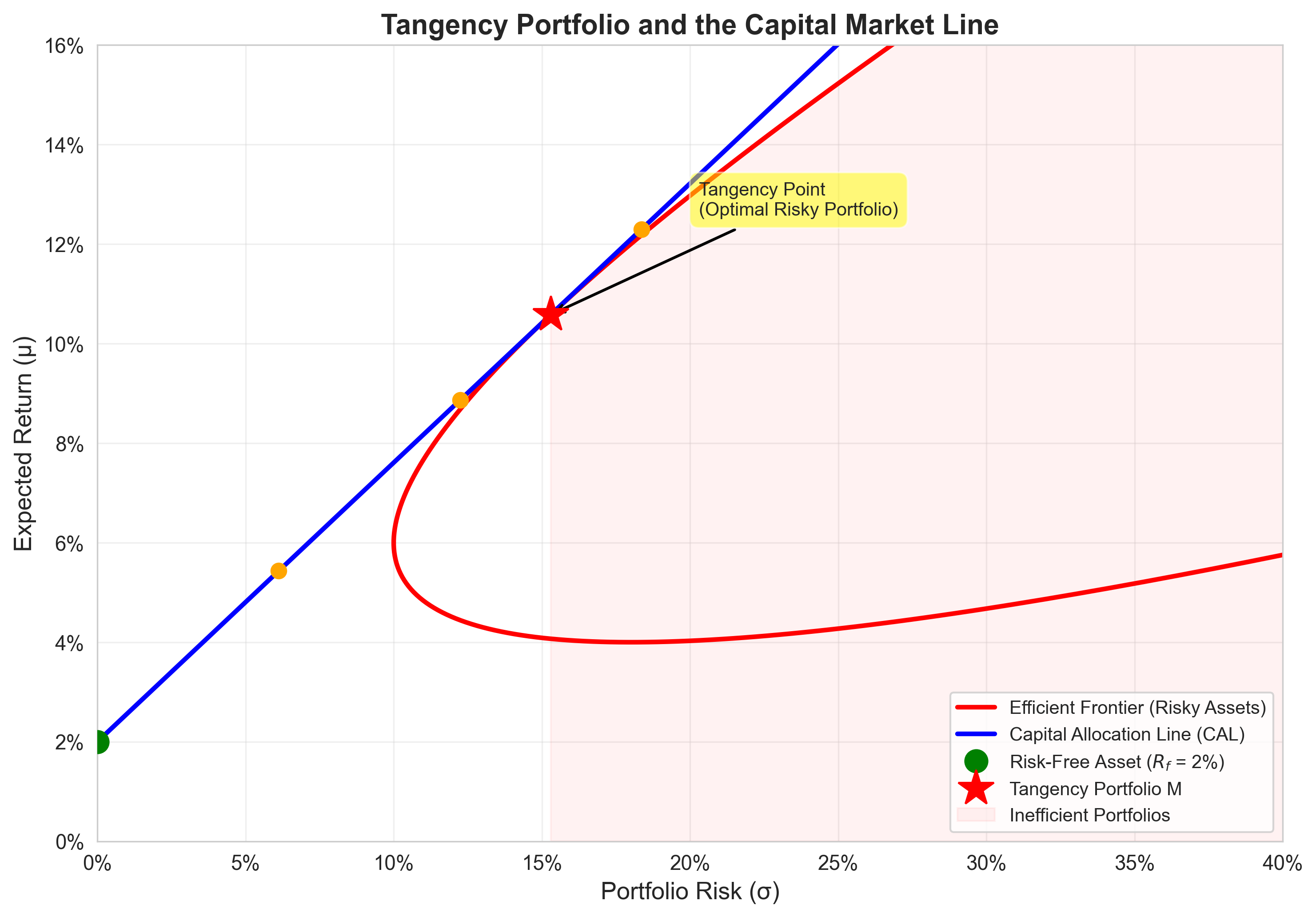

4. Many Risky Assets + Risk-Free Asset

When multiple risky assets exist:

Step 1: Form the optimal risky portfolio \(M\) from all risky assets

- This portfolio has expected return \(\mu_M\) and risk \(\sigma_M\)

- It lies on the efficient frontier of risky assets

Step 2: Combine \(M\) with the risk-free asset

- Choose weight \(w\) in \(M\) and \((1-w)\) in \(R_f\)

The CAL becomes:

\[ \mu_p = R_f + \frac{\mu_M - R_f}{\sigma_M} \sigma_p \]

This line is tangent to the efficient frontier of risky assets.

The Two-Fund Separation Theorem

Theorem: Every investor, regardless of risk preferences, holds:

- The same optimal risky portfolio \(M\)

- Some amount of the risk-free asset

Only the mix \((w, 1-w)\) differs across investors.

Implications:

- Preferences determine how much risk to take

- Preferences do not determine which risky assets to hold

- All investors agree on the composition of \(M\)

This is one of the most powerful results in finance.

It justifies index funds and passive investing.

Graphical Illustration: Tangency Portfolio

- The tangency portfolio \(M\) maximizes the Sharpe ratio

- The CAL from \(R_f\) through \(M\) dominates all other combinations

- All efficient portfolios lie on this single line

The geometry reveals the economics.

5. Investor Preferences

To choose among portfolios on the CAL, we need a model of preferences.

Finance borrows this machinery from economics.

We assume investors care about:

- Expected return \(\mu\) (higher is better)

- Risk \(\sigma\) (lower is better)

These two dimensions define the decision space.

Nothing exotic. Pure rationality.

Mean–Variance Utility Function

Preferences are represented by a utility function:

\[ U(\mu, \sigma^2) = \mu - \frac{\gamma}{2}\sigma^2 \]

Where:

- \(U\) = utility (satisfaction level)

- \(\mu\) = expected return

- \(\sigma^2\) = variance

- \(\gamma > 0\) = risk aversion coefficient

Interpretation:

- Utility increases with expected return

- Utility decreases with variance

- \(\gamma\) measures the trade-off rate

This is not psychology.

It is tractable mathematics.

Risk Aversion Parameter \(\gamma\)

The parameter \(\gamma\) determines risk tolerance.

Large \(\gamma\): High risk aversion

- Steep penalty for variance

- Preference for safer portfolios

Small \(\gamma\): Low risk aversion

- Mild penalty for variance

- Willingness to accept more risk

\(\gamma \to \infty\): Extreme risk aversion

- Only risk-free asset is acceptable

\(\gamma \to 0\): Risk neutrality

- Only expected return matters

Different investors = different \(\gamma\) values.

Same mathematics, different parameters.

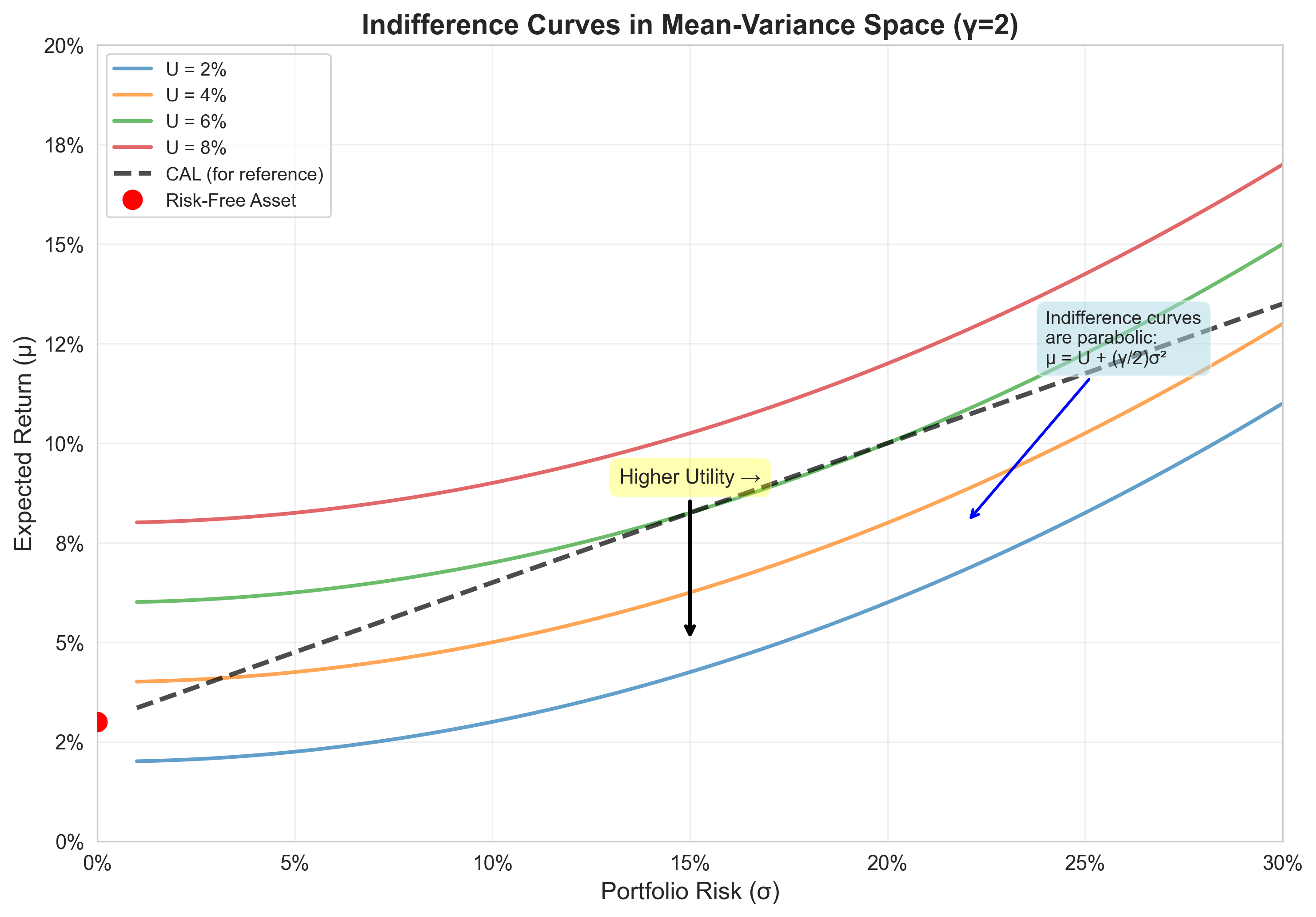

6. Indifference Curves

An indifference curve is the set of \((\sigma, \mu)\) pairs yielding equal utility.

Set \(U\) to a constant \(\bar{U}\):

\[ \bar{U} = \mu - \frac{\gamma}{2}\sigma^2 \]

Solve for \(\mu\):

\[ \mu = \bar{U} + \frac{\gamma}{2}\sigma^2 \]

This is a parabola in \((\sigma, \mu)\) space.

Opening upward, with vertex on the \(\mu\)-axis.

Properties of Indifference Curves

Upward sloping

- To compensate for higher risk, higher return is required

- Slope: \(\frac{d\mu}{d\sigma} = \gamma\sigma > 0\)

Convex (increasingly steep)

- \(\frac{d^2\mu}{d\sigma^2} = \gamma > 0\)

- Marginal rate of substitution increases with risk

Do not intersect

- Would violate transitivity of preferences

Higher curves = higher utility

- Investors prefer portfolios on higher curves

Geometry replaces psychology.

Graphical Representation

- Each curve represents constant utility

- Curves further northeast = higher utility

- Steepness reflects risk aversion

- Never intersect (consistency of preferences)

The investor seeks the highest attainable curve.

Derivation: Slope of Indifference Curve

From \(U = \mu - \frac{\gamma}{2}\sigma^2\), differentiate implicitly holding \(U\) constant:

\[ dU = 0 = d\mu - \gamma\sigma \, d\sigma \]

Rearranging:

\[ \frac{d\mu}{d\sigma} = \gamma\sigma \]

Interpretation:

- The slope is the marginal rate of substitution between risk and return

- It increases with \(\sigma\) (convexity)

- It increases with \(\gamma\) (risk aversion)

At \(\sigma = 0\): Slope is zero (flat)

- No risk, no required compensation

As \(\sigma\) increases: Slope rises

- Higher risk demands disproportionately higher return

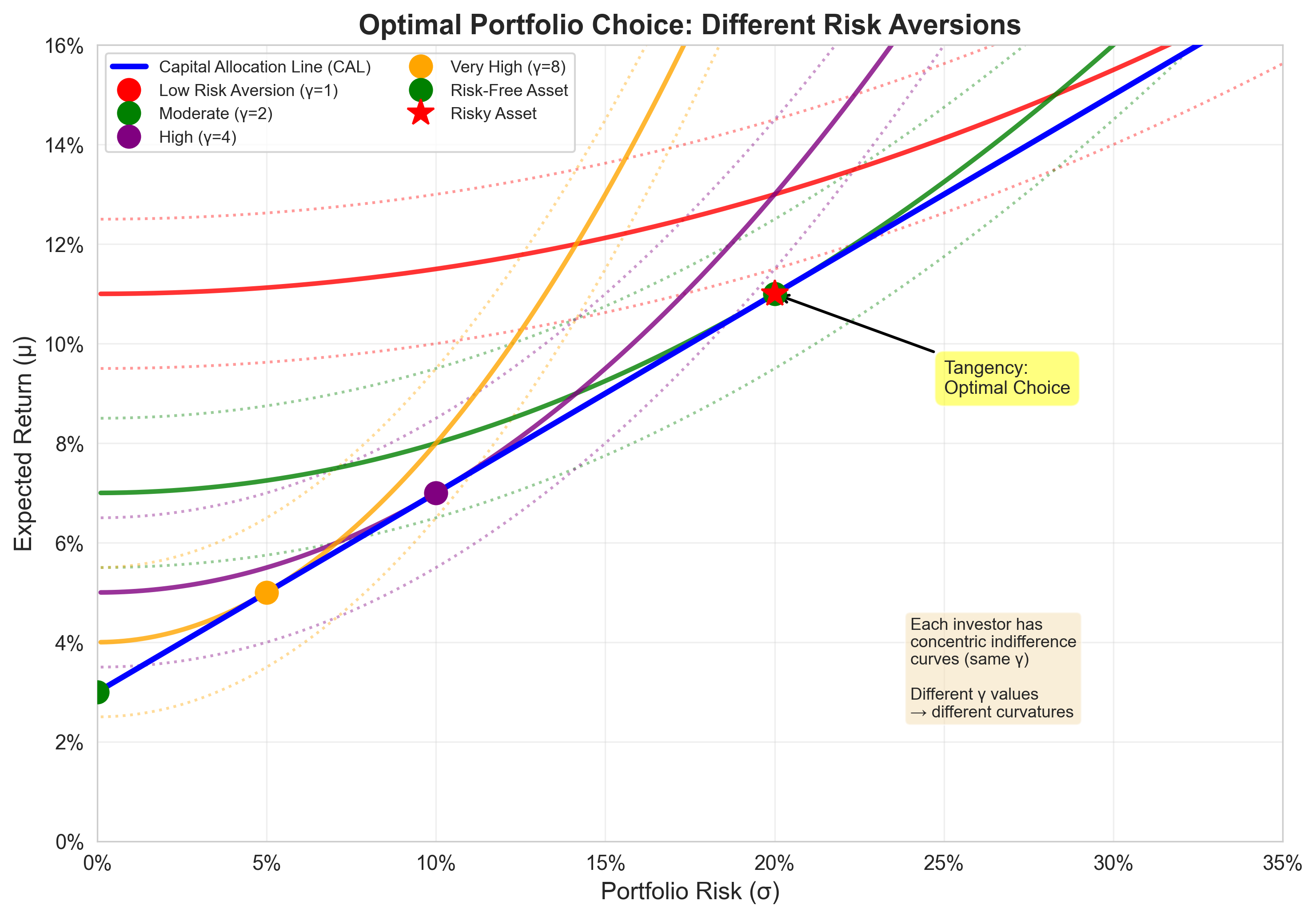

7. Optimal Portfolio Choice

The investor's problem:

\[ \max_{w} \quad U(\mu_p, \sigma_p^2) = \mu_p - \frac{\gamma}{2}\sigma_p^2 \]

Subject to:

- \(\mu_p = R_f + w(\mu - R_f)\)

- \(\sigma_p = w\sigma\)

Substitute into utility:

\[ U(w) = R_f + w(\mu - R_f) - \frac{\gamma}{2}(w\sigma)^2 \]

This is an unconstrained optimization problem in \(w\).

Solving for Optimal Weight

Take the first-order condition:

\[ \frac{dU}{dw} = (\mu - R_f) - \gamma w \sigma^2 = 0 \]

Solve for \(w^*\):

\[ \boxed{w^* = \frac{\mu - R_f}{\gamma \sigma^2}} \]

Interpretation:

- Optimal exposure increases with risk premium \((\mu - R_f)\)

- Optimal exposure decreases with risk aversion \(\gamma\)

- Optimal exposure decreases with variance \(\sigma^2\)

This is the fundamental portfolio allocation formula.

Second-Order Condition

Check the second derivative:

\[ \frac{d^2U}{dw^2} = -\gamma \sigma^2 < 0 \]

Since \(\gamma > 0\) and \(\sigma^2 > 0\), the second derivative is negative.

Therefore, \(w^*\) is a maximum, not a minimum.

The solution is verified.

Numerical Example

Suppose:

- \(R_f = 3\%\)

- \(\mu = 10\%\)

- \(\sigma = 20\%\)

- \(\gamma = 2\) (moderate risk aversion)

Optimal weight:

\[ w^* = \frac{0.10 - 0.03}{2 \times 0.20^2} = \frac{0.07}{2 \times 0.04} = \frac{0.07}{0.08} = 0.875 \]

Interpretation:

- Invest 87.5% in the risky asset

- Invest 12.5% in the risk-free asset

Portfolio characteristics:

- \(\mu_p = 0.03 + 0.875(0.10 - 0.03) = 0.09125 = 9.125\%\)

- \(\sigma_p = 0.875 \times 0.20 = 0.175 = 17.5\%\)

Sensitivity Analysis

How does \(w^*\) change with parameters?

\[ w^* = \frac{\mu - R_f}{\gamma \sigma^2} \]

Higher risk premium \((\mu - R_f)\) → Higher \(w^*\)

- Better rewards justify more risk

Higher risk aversion \(\gamma\) → Lower \(w^*\)

- More cautious investors take less risk

Higher volatility \(\sigma\) → Lower \(w^*\)

- Riskier assets warrant smaller positions

These relationships are intuitive.

The mathematics merely formalizes common sense.

Graphical Solution: Tangency Condition

The optimal portfolio occurs where:

- An indifference curve is tangent to the CAL

At the tangency point:

- Slope of CAL = Slope of indifference curve

CAL slope: \(\frac{\mu - R_f}{\sigma}\)

Indifference curve slope: \(\gamma \sigma_p = \gamma w^* \sigma\)

Setting them equal:

\[ \frac{\mu - R_f}{\sigma} = \gamma w^* \sigma \]

Solving for \(w^*\):

\[ w^* = \frac{\mu - R_f}{\gamma \sigma^2} \]

Geometry and calculus agree.

As they must.

Graphical Representation

- Different investors have different indifference curves (different \(\gamma\))

- All face the same CAL (same market opportunities)

- Each chooses the tangency point on their indifference curve

- Higher risk aversion → tangency at lower \(\sigma\) (more conservative)

Same risky portfolio.

Different mixing proportions.

This result is deep, old, and still misunderstood.

16. Exercises

Exercise 1: Optimal Portfolio with Risk-Free Asset

Given:

- Risk-free rate: \(R_f = 2\%\)

- Risky asset expected return: \(\mu = 9\%\)

- Risky asset standard deviation: \(\sigma = 15\%\)

- Risk aversion: \(\gamma = 3\)

Tasks:

- Derive the optimal weight \(w^*\) in the risky asset

- Calculate the expected return and risk of the optimal portfolio

- How does \(w^*\) change if \(\gamma\) doubles?

Exercise 2: Indifference Curves

An investor has utility function \(U = \mu - 2\sigma^2\).

Tasks:

- Derive the equation of an indifference curve with utility \(U = 0.05\)

- Calculate the slope of this curve at \(\sigma = 0.10\)

- If the CAL has slope \(0.4\), at what value of \(\sigma\) does tangency occur?

- What is the optimal portfolio return at this tangency?

Exercise 3: Two-Asset Efficient Portfolio

Two assets have:

- \(\mu_1 = 6\%\), \(\sigma_1 = 12\%\)

- \(\mu_2 = 14\%\), \(\sigma_2 = 25\%\)

- \(\rho_{12} = 0.2\)

Tasks:

- Find the weights for a portfolio with target return \(\mu_p = 10\%\)

- Calculate the variance of this portfolio

- Find the minimum variance portfolio (no target return)

- Compare the two portfolios' risk levels

Exercise 4: Sharpe Ratio Maximization

Prove that the tangency portfolio (from \(R_f\) to the efficient frontier) maximizes the Sharpe ratio among all risky portfolios.

Hint: Use the fact that at tangency, the slope of the CAL equals the slope of the efficient frontier.

Tasks:

- Set up the optimization problem

- Use Lagrange multipliers to find the tangency portfolio

- Show that this portfolio has the highest Sharpe ratio

- Interpret the result economically

Final Takeaways

Adding a risk-free asset transforms portfolio theory:

- Efficient frontier becomes a straight line (CAL)

- All investors hold the same risky portfolio (two-fund separation)

- Only the risk-free/risky mix differs across investors

Preferences formalize decision-making:

- Mean-variance utility captures risk-return trade-offs

- Indifference curves visualize preferences geometrically

- Risk aversion determines portfolio allocation

Optimal choice is a tangency condition:

- Graphically: indifference curve tangent to CAL

- Analytically: \(w^* = \frac{\mu - R_f}{\gamma \sigma^2}\)

- Same intuition, different representations

Lagrange multipliers are unavoidable:

- Every constrained optimization uses this method

- Multipliers have economic interpretations (shadow prices)

- Foundation for all advanced portfolio theory

Theory guides practice:

- These results justify index funds and passive strategies

- Risk parity, factor models, and dynamic allocation all build on this foundation

- Mathematics reveals economic truth

Next lecture: We extend this framework to multi-asset portfolios and derive the full efficient frontier.